The Royal Navy of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was the largest maritime force in the world, but it faced a constant problem…men.

Keeping the fleet manned in wartime demanded tens of thousands of sailors, far more than could be drawn from the ranks of volunteers.

Why?

Pay was low, conditions were harsh, and merchant service offered better wages with fewer risks. To fill the gap, the Admiralty turned to a system that was both feared and notorious…the press gang.

The legal basis for pressing men into service went back centuries. In theory, the Crown claimed the right to call on seafaring men for defence.

During the reign of Elizabeth I, warrants were issued authorising officials to compel mariners to join the fleet in times of need. By the seventeenth century this had hardened into a regular practice, accepted in law if not in popular opinion.

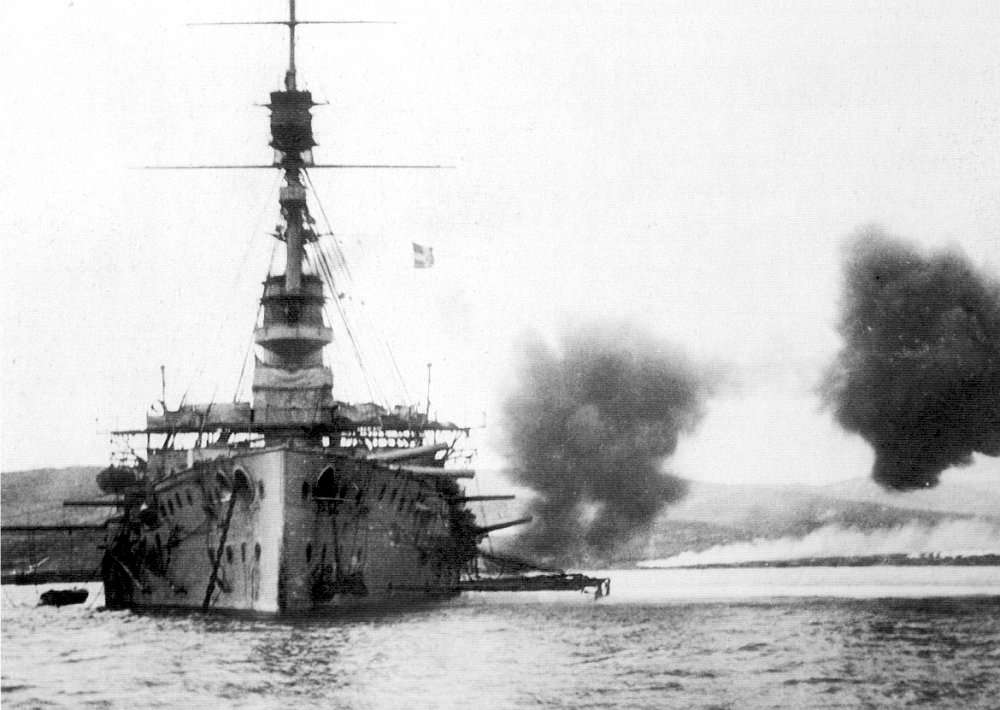

Impressment, as it was formally known, reached its peak during the wars against France from 1793 to 1815, when the Royal Navy expanded on a scale never seen before.

Structure

A press gang was usually made up of a lieutenant, a midshipman or two, and a handful of armed seamen. They carried an impress warrant, authorising them to seize men judged suitable for naval service.

In practice, “suitable” was a loose term. Seafaring experience was the main requirement, but gangs did not always restrict themselves to hardened sailors.

Labourers from the docks, fishermen, and even young apprentices might find themselves dragged off to a waiting tender.

The methods of the press gang were blunt. Men were seized in alehouses, on the quayside, or even in the street. A sudden rush of armed tars would surround the target, the warrant was waved, and resistance usually met with the butt of a musket or a cutlass flat.

Though the gang acted under royal authority, violence was common, and riots against the press were frequent. Coastal towns such as Whitby, Yarmouth, and Plymouth all saw pitched battles between press gangs and angry locals.

Necessity

Not every impressment ended in struggle. Some men accepted the King’s shilling when it was pressed into their palm, and others volunteered on the spot to avoid the rougher handling that came with resistance.

Once taken, recruits were held aboard tenders anchored in harbour until enough had been gathered to send on to a warship. Conditions on these holding vessels were often grim, with poor food and crowded decks.

The Navy justified the press as a matter of necessity. Without it, they argued, the fleet could not be manned in time of war.

A line-of-battle ship needed 600 to 800 men, and with dozens of new ships launched during the wars with France, the manpower demands were immense. At its height in the Napoleonic Wars, the Navy employed around 140,000 sailors…a figure impossible to maintain by volunteers alone.

Brute Force

Press gangs became a symbol of naval tyranny ashore. Ballads, pamphlets, and political cartoons of the period show the fear they inspired. Stories of men torn from their families or seized as they left church on Sunday circulated widely.

Some towns went so far as to raise their own watches to warn when a gang was about. The practice created deep resentment among the working population, though it was tolerated by governments as a grim necessity.

Not all men pressed into service stayed against their will. Life aboard a man-of-war was hard, but it offered regular meals, medical care of a sort, and prize money when enemy ships were captured. For some, a pressed start became a naval career.

Others deserted at the first chance. Impressment remained a gamble for both sides: the Navy gained bodies, but not always willing or reliable seamen.

Demise

The end of the press gang came only when manpower pressures eased. After 1815, with the defeat of Napoleon, the Royal Navy shrank dramatically. Volunteers were sufficient for the reduced fleet, and impressment lapsed into disuse.

The legal power to press was never formally abolished, but by the mid-nineteenth century it was a relic, remembered more in song and story than in practice.

Today the press gang remains one of the darker chapters of Britain’s naval past. It kept the fleet afloat during wars that shaped Europe, but at a heavy social cost.

To men in ports and coastal towns it meant fear of sudden loss, and to the Navy it meant filling its ships with unwilling hands. The practice may have won battles at sea, but it left scars ashore that lingered long after the guns fell silent.